With a flash of lightning and a clap of thunder, the Hendrix Fire began on July 16, 2018. The fire was lit on Garvin Gulch, a small tributary of Glade Creek in the Little Applegate River watershed. It began on the lower flank of Sevenmile Ridge’s western face, at the boundary of Forest Service and clearcut, private industrial forest land.

Sevenmile Ridge is a prominent feature in the upper Little Applegate River watershed. It extends south from the Little Applegate River near Brickpile Ranch, to the broad, barren serpentine summit of Big Red Mountain on the Siskiyou Crest. Big Red Mountain contains incredible botanical diversity and numerous rare plant populations, protected in both the Big Red Mountain Botanical Area and Research Natural Area. Big Red Mountain is cherished by many people in southern Oregon and northern California as the most intact portion of the Little Applegate River watershed, and one of the most botanically diverse mountains on the eastern Siskiyou Crest.

From the summit of Big Red Mountain, Sevenmile Ridge drops north, supporting dense fields of beargrass, sparse grasslands, low rock outcrops, serpentine pine forests and ancient mixed conifer forests. Unfortunately, these beautiful and intact forests are broken by swaths of clearcut, private lands that straddle the ridgeline. Much of the Hendrix Fire burned in this mixture of intact Forest Service land and recently logged private timberland. Large portions of the fire also burned within the 2001 Quartz Fire footprint.

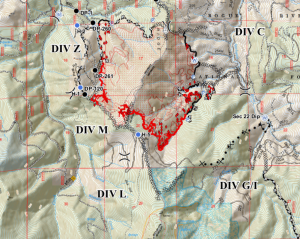

The Hendrix Fire burned actively for only about six days. In fact, over one-third of the acres burned on July 17 alone, when 344 acres burned and the fire surged up Garvin Gulch and over Sevenmile Ridge. In total, 1,082 acres burned at mixed severity, leaving a complex mosaic of living green forest, freshly burned and now rejuvenated brushfields and burned snag forests of fire-killed trees.

From the beginning, Forest Service and Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) crews began working to suppress the fire by preparing roads and building dozerlines in Garvin Gulch and near Hells Peak at the southwest and northwest fire perimeter. They also started bulldozing the old Sevenmile Ridge Trail through some of the most intact conifer forest in the area. They were heading north from the headwaters of Garvin Gulch, hoping to contain the fire at the top of Sevenmile Ridge with a long ridgetop dozerline; however, high winds pushed the fire east and it spotted over Sevenmile Ridge, becoming established in the headwaters of the Little Applegate River. At this point the dozerline on the spine of Sevenmile Ridge was deemed unnecessary and abandoned.

The fire then backed into the Little Applegate River and grew very slowly up Sevenmile Ridge towards Big Red Mountain. It was still quite early in the season and the higher elevation fuels were still very moist, helping to minimize both fire behavior and spread. The fire crept forward as crews began bulldozing south on the Sevenmile Ridge Trail into the Big Red Mountain Botanical Area.

According to Forest Service staff, portions of this dozerline were built without the permission of Forest Service officials, by either a renegade or poorly informed bulldozer operator. Either way, it was a lack of agency oversight that allowed this dozerline to be created within the Big Red Mountain Botanical Area. Roughly one mile of dozerline was built either on the boundary of the Big Red Mountain Botanical Area or within its protected boundaries, doing great damage to the otherwise intact native plant communities. Ironically, this fireline was never used for fire containment.

To their credit, Forest Service Resource Advisors (READS) working on the fire to protect natural resources, did steer crews around rare or unusual plant populations and stopped the unauthorized bulldozing before it continued further towards Big Red Mountain and the Pacific Crest Trail.

At this point, the Hendrix Fire was moving southeast, backing east off Sevenmile Ridge into dozerlines and roads on nearby private timberland, and south into a deep, forested drainage. The fire backed into this small, moist drainage, where it stalled out at the canyon bottom. After July 25, the fire sustained no new fire growth and simply smoldered out in the moist drainage. Due to steep and rugged terrain crews did not build handline or actively fight the fire in this canyon. They simply monitored the fire, making sure it did not cross the small creek; ready to act if necessary, but allowing the fire to naturally extinguish itself in the moist little streambed.

For much of the fire period heavy smoke inversions moderated fire behavior, leading to low-severity fire effects; however, the majority of the July 17 wind- and terrain-driven fire run burned at high severity. This uphill run accounts for over 1/3 of the fire area and burned through old-growth mixed conifer forest. The run began in upper Garvin Gulch and extended over Sevenmile Ridge, creating significant mortality and high-severity fire effects.

The mosaic of the Hendrix Fire is highly varied. While portions of the fire burned at low severity in stands of old-growth pine and fir, as well as in open serpentine woodlands, it also appears that significant portions of the fire did burn at relatively high severity. These high-severity fire effects are centered around the steep headwaters of Garvin Gulch and in the young plantation stands in adjacent private timberlands.

Photo: Frank Lospalluto

The mature fire-killed forests will create important snag forest habitat and is already attracting a diversity of woodpeckers, including the beautiful, and locally uncommon, white-headed woodpecker. This interesting woodpecker is found mostly east of the Cascade Mountains in dry conifer forests. Here in the eastern Siskiyou Mountains white-headed woodpeckers have stable populations around Mt. Ashland and Big Red Mountain. They have congregated in the post-fire snag forests, happily pecking insects and vocalizing cackles and calls. Research conducted following the 2001 Quartz Fire in the Little Applegate showed that high-severity snag patches create important habitat for song birds. They will also be important habitat for deer and elk, who will eat the nutritious regenerating grasses, herbs and shrubs. Black bears will come for berries, greens and bulbs. Even Northern spotted owl may forage in fire-killed snag patches for dusky footed woodrats in the newly opened, early-seral habitat.

These complex, early-seral plant communities contain important wildlife habitat and extremely high levels of biodiversity. Although often underappreciated, these snag forests are an important piece of Siskiyou Mountain biodiversity.

ANN will work to protect the important habitat the Hendrix Fire is providing on public land. We will oppose any post-fire logging that might be proposed and continue fire ecology education efforts in the Applegate Valley and in the Siskiyou Mountains. Please consider supporting our work!