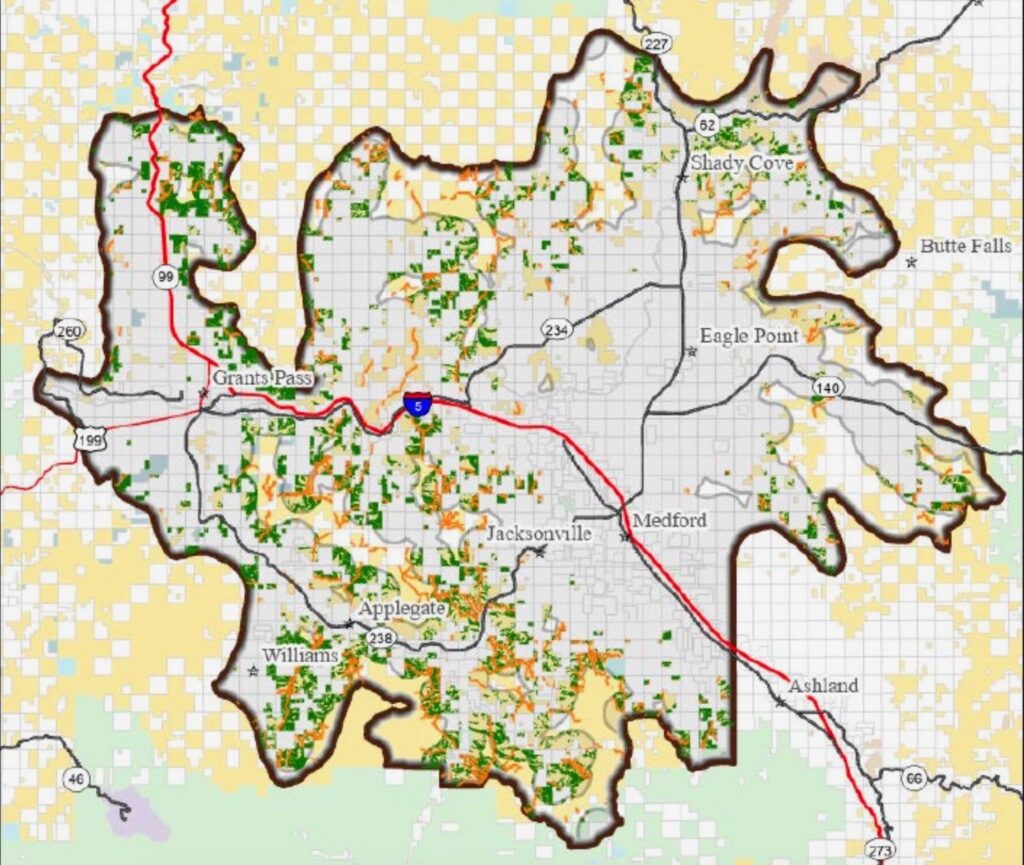

NOTE: The Medford District BLM had previously proposed and analyzed the Strategic Operations for Safety (SOS) Programmatic project, and issued an Environmental Assessment for that project. That “programmatic” project that would have approved projects across large portions of Medford District BLM lands, but that project has been DROPPED. This new project, unfortunately, has a similar name, which makes things confusing. This new project, is just focused on the Applegate and is called the Ashland 2025 SOS Project, because it is in the BLM’s Ashland Field Office.

The Ashland 2025 SOS Project Proposal

The Medford District BLM has recently proposed the Ashland 2025 SOS Project, a strangely misleading project that has nothing to do with the town of Ashland and everything to do with logging the forests of the Applegate Valley. This massive project proposes to log both the dead standing snags created in recent flat headed fir borer outbreaks and many of the live trees that survived the outbreaks.

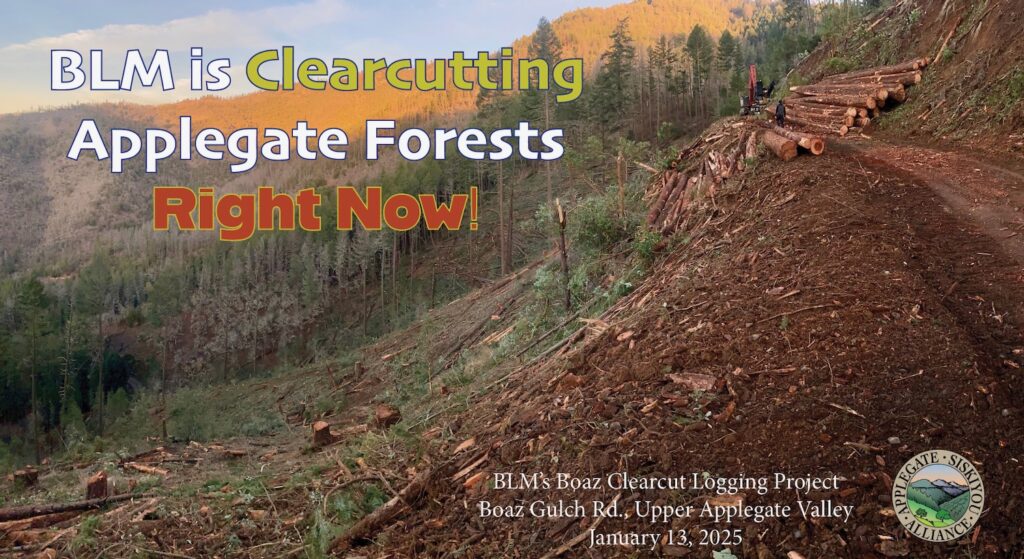

Using the recent beetle mortality outbreaks in southwestern Oregon to encourage widespread industrial logging, the project proposes logging similar to the recent “salvage” logging operations implemented in the Upper Applegate, Little Applegate, and Forest Creek areas in the Lickety Split, Boaz Salvage, and Forest Creek Salvage Timber Sales.

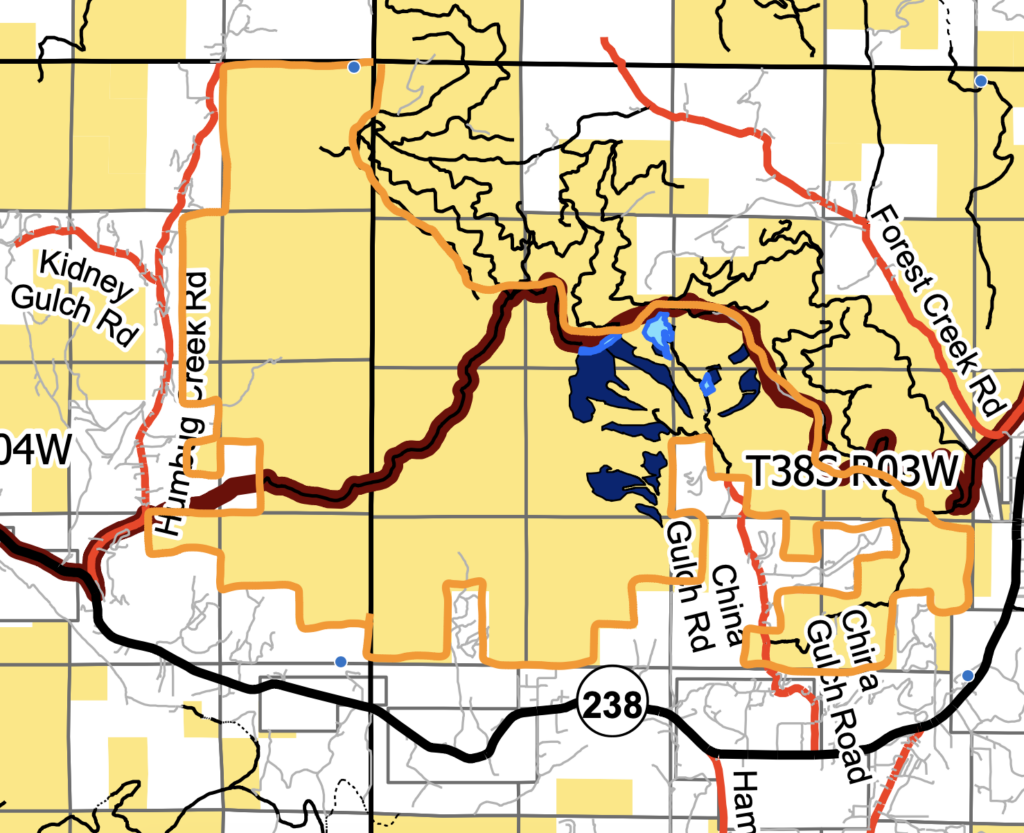

The SOS Project Will Log 5,359 Acres in the Applegate

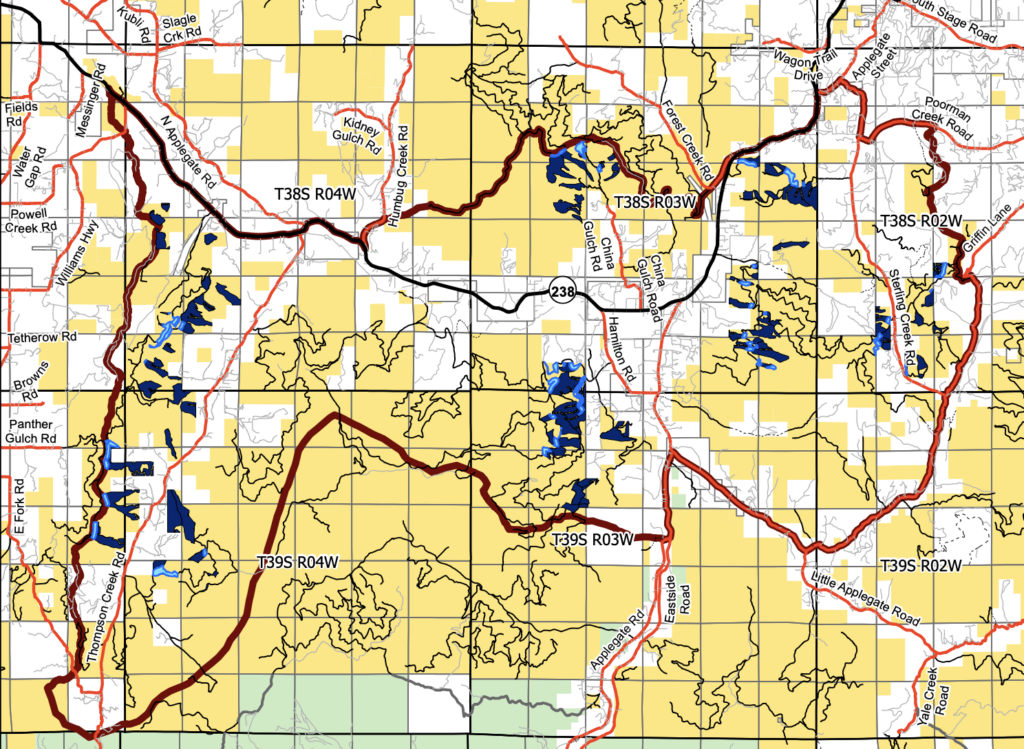

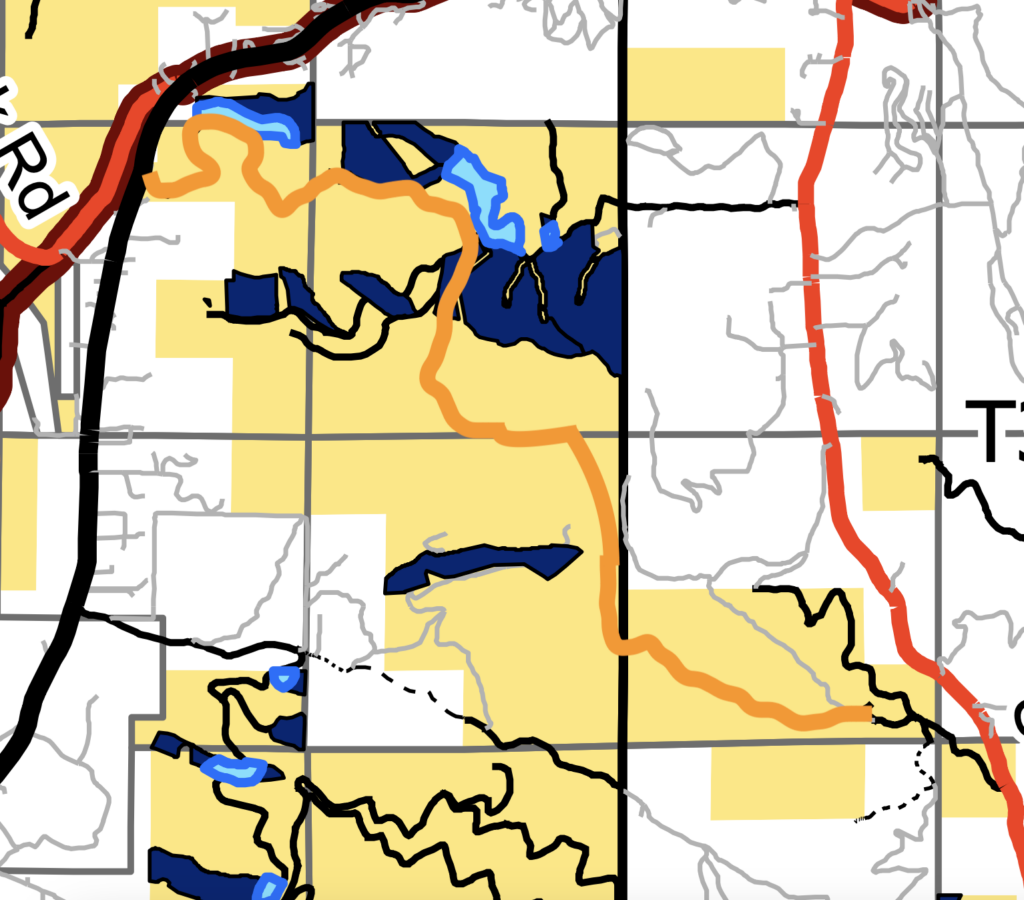

Unfortunately, this new, proposed SOS Project is much larger than the recently completed timber sales just listed. The Ashland 2025 SOS Project will log 5,359 acres on Thompson Creek, in the Wellington Wildlands at the top of China Gulch, on Ben Johnson Mountain above Cantrall Buckley County Park, on the face of Woodrat Mountain adjacent to the paragliding launch sites above Ruch, on the East Applegate Ridge Trail—the region’s signature low elevation non-motorized trail—and on Sterling Creek.

Although the BLM claims the Ashland 2025 SOS Environmental Assessment will target only dead and dying trees in its logging units, the interpretation of “dying” has been used quite liberally and without accountability. In fact, whole groves of living, viable trees would be logged under the guise of “salvage” logging, including stands with as little as 10% recent mortality. The project proposes the removal of the vast majority of trees in many of the units and would retain as little as 5%-10% canopy cover.

The SOS Project Will Increase Fire Risks in the Applegate

If authorized and implemented by BLM, the canopy reduction proposed, along with large tree logging and other significant habitat alterations would degrade forest habitats already stressed by climate change, damage important wildlife habitats, and impact local watersheds. Contrary to the claims of the BLM, the project would also dramatically increase fire risks by creating a dense regenerative response, by removing large fire, beetle and drought resistant live trees, and by converting once protected forest microclimates into hot, sunbaked shrubfields with significantly higher fire risks.

Dangerously, the SOS Project would surround rural residential communities in the Applegate Valley with increased fire risks and habitat conditions that can fuel fast moving, high intensity fire through the deposition of logging slash, the regeneration of dense, even-aged, highly flammable vegetation, and the removal of the trees and conditions that favor more slow moving, low to moderate intensity fire.

Anyone with experience in the forests of southwestern Oregon knows that when you remove a mature forest canopy you create hotter, drier slopes with significantly higher fire risks. For example, in 2018 the BLM analyzed the Clean Slate Timber Sale east of Selma, Oregon and found:

“For the first 1 to 5 years after harvest, these stands would remain a slash fuel type until the shrubs, grasses, and planted trees become established. After the establishment of regeneration, these stands would move into a brush fuel type. Brush fuel types are more volatile and are susceptible to high rates of fire-caused mortality. Stands could exhibit higher flame lengths, rates of spread, and fire intensity. Fires started within these stands could be difficult to initially attack and control. For 5 to 20 years following planting, the overall fire hazard would increase in these stands.”

The SOS Project would log in mature stands with minimal tree mortality, but it would also include some stands with higher levels of recent beetle mortality. In these stands, the BLM is proposing to log both dead standing and living trees, and the project would also damage and/or destroy hardwoods, younger vegetation, and living mature conifer trees during the felling, yarding and tree removal process. It will also damage, compact and disturb forest soils which could lead to sedimentation and landslides like those that recently occurred in the Boaz Salvage Timber Sale above the Upper Applegate Valley.

The SOS Project Will Degrade Applegate Valley Views

If the SOS Project is approved the viewsheds of the Applegate Valley would be badly degraded, including along the Highway 238 corridor, on beloved non-motorized trails like the East Applegate Ridge Trail, on the Woodrat Mountain Paragliding Launch Sites, in the Wellington Wildlands, and from nearly every vineyard tasting room and residence in the Ruch area.

Snag Habitat is Important Habitat

Yet, the impact is far more than aesthetic, and the logging proposed would leave lasting negative impacts on the ecology of Applegate forests. The SOS Project would impact mature, living forests that provide important habitat for species like the northern spotted owl, the great grey owl, and the Pacific fisher. Removing mature, relatively complex, closed-canopy forests and replacing them with a scattering of large overstory trees and dense regenerating forest vegetation does not benefit these species, does not support “forest health” as the BLM claims, and has very little to do with the so-called “salvage” of dead standing trees.

Additionally, the removal of standing snags and snag patches, where they do not pose a risk to public safety or infrastructure is proposed throughout the SOS Project. This would dramatically alter these habitats and the complexity of forest regeneration. It would also remove the significant flush of snags created by recent beetle mortality. These snags and the subsequent downed wood they represent are the only input of these habitats that affected stands will support until the forest again grows trees large enough to develop and restore large snag and downed wood supplies.

The dead standing snags and downed wood created by beetle outbreaks are important forest structures for wildlife who disproportionately utilize large commercial sized snags for denning, nesting, rearing young, and resting or perching. Snags and downed logs are utilized by an incredible number of wildlife species, including black bears, Pacific fisher, cougars, coyote, numerous woodpecker species, song birds, raptors of all sorts, bats, terrestrial salamanders, butterflies, bees and other pollinators, and numerous aquatic species, including endangered Western pond turtles, the Pacific giant salamander, and endangered anadromous fisheries. From a biological perspective snags, downed wood and instream wood are not a liability, they are a necessity for so many species and BLM logging in the SOS Project would create long-term shortages in snags, downed wood, and forest complexity .

The Flat Headed Fir Borer Outbreak Has Subsided

Finally, the episodic flat headed fir borer beetle mortality event that BLM claims to be responding to in the SOS Project has subsided, and even a casual observer will notice that little new mortality is occurring in the spring of 2025. The heavy rains of this past winter should help mitigate the affects of summer drought on these landscapes and beetle populations have crashed when compared to the spring of 2023.

Look around the valley and its forested foothill slopes. Do you see swaths of “red” or “bronze” trees dying out as they were in 2022 and 2023, or do you mostly see the “gray” snags of years past? The BLM claims we are still in the midst of this outbreak and masses of living, green trees will soon die from beetle infestation. Yet, beetle populations have been dramatically reduced since 2023 and beetle mortality has returned to background levels, or near background levels.

We have seen this cycle in the Applegate many times over the years, and it is just part of the natural cycle. Being located in the driest major watershed in Western Oregon, many forest habitats in the Applegate foothills are on the margin and often grow within a patchwork of oak, madrone, canyon live oak and other hardwood species, arid grasslands, and chaparral. In moist years Douglas fir grows well in the Applegate, but in dry periods heavy losses from drought stress and beetle outbreaks can occur. For example, on Thompson Creek and Ferris Gulch in 2016, large outbreaks occurred and subsided, and these forests were less affected by the outbreaks in 2022 and 2023 and have demonstrated increased resilience. In many locations, the stands on Thompson Creek and Ferris Gulch have also begun to naturally recover with a diversity of pine, fir and young hardwoods growing in the canopy gaps created by flat headed fir borer mortality in 2016.

Additionally, only a portion of the Applegate tends to be heavily affected by large outbreaks of flat headed fir borer beetles, as the more moist part of the watershed demonstrate more resilience. More moist areas in the western Applegate Valley, at mid to high elevation areas, in drainages and canyon bottoms, and to some extent north and east facing slopes at lower elevations can all act as refugia and sustain far less mortality during regional drought cycles. Currently the mortality is centered around the eastern Applegate Valley near around Applegate, Ruch, Sterling Creek, Little Applegate Valley, and portions of the Upper Applegate Valley.

It is also important to note that the cumulative mortality created by proposed BLM logging operations would significantly exceed the level of natural mortality in affected timber sale units, and rather than mitigating the beetle mortality event, the agency is only adding to it by logging living trees across over 5,000 acres in the Applegate River watershed.

The BLM Has a Poor Track Record With “Salvage” Logging in the Applegate

The science shows that logging large old trees and removing snags following wildfires or beetle outbreaks does not reduce fire risks, benefit wildlife, or increase forest health. Recent salvage logging timber sales in the Applegate Valley have converted once living, green forests and beetle killed snag patches filled with vibrant natural regeneration into grayish-brown scars denuded of nearly all vegetation and cleared of virtually all habitat complexity. The results can be seen up Lick Gulch in the Little Applegate, on Cinnabar Ridge above both the Upper Applegate and Little Applegate Valleys, on Boaz Mountain, and in the Forest Creek watershed where recent BLM “salvage” projects have been implemented.

What you will find in these recently implemented “salvage” timber sales are raw, eroding, denuded slopes, stripped of their biological legacies and forest canopies, cleared of most vegetation, churned to bare ground by dozer treads, deeply rutted with vertical skyline yarding scars, streaked in landslides, and littered with logging slash.

The SOS Project is a timber grab plain and simple, and it would have devastating impacts to our region.

Please comment on the BLM’s Ashland 2025 SOS Project and let them know the forests and even the snags in many portions of the Applegate are worth more standing.

Comments are due by June 23, 2025! Please help us protect the Applegate and submit comments by clicking on this link

Read the EA and find other information on the BLM’s SOS Project site. Click on participate now to comment!

Talking Points for Public Comment:

- Logging stands with as little as 10% tree mortality is counterproductive. In those stands with relatively minimal recent mortality the BLM is inappropriately merging commercial thinning treatments and “salvage” logging prescriptions to increase timber harvest, reduce canopy cover retention, limit overstory tree retention, and implement increasingly severe green tree logging treatments that violate the BLM’s 2016 Resource Management Plan (RMP).

- The SOS Project proposes a dramatic reduction in canopy cover to as low as 5%-10%. Large tree removal and excessive canopy reduction would lead to increased fire risks, dense even-aged growth, hot, dry microclimates, more extreme fire behavior, and increased rates of spread in local wildland fires.

- All logging treatments in all Land Use Allocations, including the Timber Harvest Land Base, are required to reduce fire risks in the 2016 RMP, yet the SOS Project would dramatically increase fire risks due to intensive logging operations, canopy loss, large tree removal, and the subsequent development of dense shrub and tree regeneration.

- Commercial logging treatments proposed in living green stands in the SOS Project are inconsistent with dry forest management direction provided in the 2016 RMP. The 2016 RMP requires commercial thinning and Integrated Vegetation Management treatments and higher levels of tree and canopy retention than proposed in the SOS Project.

- The BLM should log no living, green trees in the SOS Project and should instead fell or remove only dead standing trees that pose a true hazard to public safety or infrastructure, including trailheads were cars will be parked, major access roads, ingress and egress routes for residential properties and major BLM roads.

- The BLM should build no new roads, “temporary” or permanent, in the SOS Project.

- The BLM should cancel all logging units in the Wellington Wildlands including units 8-3, 9-2, 17-3, 16-1, 16-1, 17-5, 17-6, 17-7, 17-8, 17-12 and adjacent Linear Treatments.

- The BLM should cancel all logging units along the East Applegate Ridge Trail and within its immediate viewshed, including units 11-1, 13-1, 13-2, 13-3, 13-4, 14-1, 14-2, 24-1, and adjacent Linear Treatments.

- The SOS Project proposes unit-based “salvage” logging that is strictly prohibited in Riparian Reserve and Late Successional Reserve forests under the 2016 RMP. All units in Riparian Reserves and Late Successional Reserves should be canceled.

- The BLM cannot “tier” to analysis that does not exists. The 2016 RMP did not analyze, model, authorize, or consider beetle or “decline” related salvage logging.

- The current analysis for the SOS Project is inadequate and a full EIS should be utilized to analyze, disclose, and consider the project’s environmental impacts. This would also allow for additional and more meaningful public comment.

- Current analysis fails to adequately consider the impact of logging on fire risks, recreation, wildlife including the Northern spotted owl, Pacific fisher and other species, water quality, and fisheries.

Which look more healthy to you? Green forests dominated by mature trees, natural regeneration in unlogged beetle mortality patches, or clearcuts and landslides in recent BLM logging projects?