Happy Winter Solstice!

To celebrate winter we wanted to highlight the diversity of conifer species in the Applegate.

The Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains are known for their incredible biodiversity and contain more conifer species than any other temperate forest in North America — 35 species. The Applegate Watershed alone contains 22 conifer species! The diversity of the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains is a result of the region’s unique geologic diversity, steep topography and pronounced microclimates, as well as dramatic elevation gradients, climatic gradients and millions of years of undisturbed evolution.

The region closest to the coast receives up to 125″ of annual rainfall, supporting dense rainforests with some of the world’s largest coastal redwoods. Roughly forty miles interior, in a pronounced rain shadow, portions of the Applegate Valley receive less than 20″ of annual rainfall, creating a unique mixture of grassland, oak woodland, chaparral, groves of western juniper and dry mixed conifer forests of pine and fir.

Forest habitats in the Siskiyou Mountains and the Applegate Valley (the Applegate Siskiyous) are widely varied depending on the soils, slope positions, aspect and elevation. Species associated with cool and moist climates cling to the canyon bottoms and north- or east-facing slopes throughout the region, while species associated with arid mixed conifer and woodland occur on south- or west-facing slopes and ridges.

At low elevations, the Applegate Watershed supports a mixture of moist Douglas fir and tanoak habitats on Slate Creek, Cheney Creek and the headwaters of Williams Creek, where a cool, coastal-influenced environment is maintained through abundant rain, relatively productive soils, and winter fog. These forests support Port Orford-cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana), a beautiful, drooping cedar with bluish foliage and layered, silvery bark. The Port Orford-cedar is endemic to the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains, growing along a 200-mile strip running north to south from Coos Bay, Oregon to Horse Mountain east of Eureka, California. In general, Port Orford-cedar populations are found within 40 miles of the Pacific Coast. In the Applegate, the Williams Creek population is at the eastern edge of the prevailing Port Orford-cedar range.

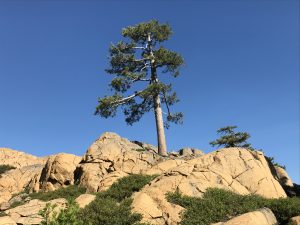

The low-elevation forests in the foothills of the Applegate Valley and east of Murphy, Oregon receive far less rainfall. These habitats support dry mixed conifer forests, mixed evergreen forest and oak woodland. In addition to supporting more common conifer species such as Douglas fir, sugar pine, and ponderosa pine, these dry habitats also support some of the western-most western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis) in the Siskiyou Mountains. Western juniper has a prevailing range that extends across the juniper steppe and high desert country to the east. On dry, exposed sites up the Little Applegate River and in the Dakubetede Roadless Area, groves of old growth juniper grow among oak woodlands, dry grasslands and stately open grown ponderosa pine. The western-most population of western juniper in the Siskiyou Mountains consists of a few trees on a west-facing slope in the Wellington Wildlands, above Humbug Creek.

These dry Applegate forests also support a remnant of the Rogue and Applegate Valley’s historic gray pine (Pinus sabiniana) populations. In the 1930s botanist Oliver Mathews documented gray pine populations near Ruch. Other small populations were found in the Rogue Valley near White City and Gold Hill, where a few trees remain today. Currently, a single mature gray pine tree is the last of the Applegate population. It grows in a small grassy clearing at the edge of the Little Grayback Roadless Area in the Upper Applegate, creating one of the northern-most populations of gray pine, a tree found more abundantly to the south, throughout California.

At higher elevations in the Applegate Watershed on the Siskiyou Crest, the snow forests of the Cascade Mountains and Sierra Nevada mingle in unique and interesting ways. Above 5,000′ Siskiyou Mountain forests are dominated by true fir species, including white fir (Abies concolor) and a confusing series of naturally occurring hybrid populations of shasta red fir (Abies magnifica var. shastensis), and red fir (Abies magnifica), which are common in the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades, and noble fir (Abies procera), which is more common to the north in the Cascade Mountains. The resulting blend of genetic diversity has created unusual hybrids with characteristics of numerous species that are hard to differentiate.

Also inhabiting the higher elevations of the Applegate Siskiyous are the region’s most ancient conifer species, holdouts from the Little Ice Age, when much of the west coast was covered in vast glaciers. In most places, botanical diversity was swallowed in dense sheets of ice, but in the Siskiyou Mountains ice-free areas provided habitat refugia for temperate forests that were once widespread some 65 million years ago. These forests are referred to as Arcto-Tertirary forests, which hang on as only remnants throughout the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains and the Siskiyou Crest.

Species such as the iconic Brewer’s spruce (Picea breweriana) and Port Orford-cedar are “paleoendemics,” remaining only in the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains. Some conifer species that grew alongside Brewer’s spruce and Port Orford-cedar 65 million years ago still reach their southern limit in the Siskiyou Mountains today. These species include trees common far north of the Siskiyous, such as Alaska yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis) and Pacific silver fir (Abies amabilis). They can be found in the high country of the Applegate Siskiyous in the Red Buttes Wilderness, the Kangaroo Roadless Area, the Condrey Mountain Roadless Area and the high country of the Upper Applegate near Whisky Peak.

As time slowly passed, the climate changed, mountains continued forming and eroding, forest communities came and went, but small islands of these Arcto-Tertirary forests remain to this day in cool, protected north slopes that act as fire refugia. Being very sensitive to drought and fire these species find sites that tend to hold snow late into the season, grow on rocky substrates and cling to dark, cool slopes were fire either fails to burn or burns in a patchy, low-severity pattern. These species have survived in the headwaters of the Applegate River through droughts and fires, into a climatic region that would be inhospitable if the trees had not found the perfect microclimates.

The rarest conifer with the most restricted range in the Siskiyou Mountains is Baker’s cypress (Hesperocyparis bakeri). Baker’s cypress has the northern-most range of any cypress in North America, and although it is also a paleoendemic species, it does not necessarily cling to cool, moist sites. Found in 11 distinct populations worldwide, each Baker’s cypress population occurs in its own unique habitat. Some grow at high elevations in the caldera of extinct volcanoes north of Mount Shasta; some occur in the relatively recent lava flows of the Pitt River, and some inhabit the nutrient deficient soils of the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains. Of the 11 populations world-wide, eight can be found in the Klamath-Siskiyous, and only one of these populations can be found in the Applegate Watershed. The Applegate Watershed’s Baker’s cypress are found in the Kangaroo Roadless Area on the Sturgis Fork of Carberry Creek, near Miller Lake, Steve’s Peak and Iron Mountain.

Great article! While I don’t think you should include the naturalized population of the ghost pine, you missed subalpine fir. http://blog.conifercountry.com/2014/07/subalpine-fir-in-the-red-buttes-wilderness/

Thanks Michael. Glad you liked the post. 22 conifers ain’t bad.

The Gray pine (or Ghost Pine) near Little Grayback is locally debated. Is it native or naturalized? We do not feel anyone can definitively say if it is a native tree or not. What we do know is that it was historically a minor component of interior SW Oregon’s flora and did grow in the Rogue Valley region in the 1850’s. John Strong Newberry, a naturalist traveling with the 1855 Pacific Railroad Survey described Gray Pine in the Rogue Valley stating ” It was found by our party in the valleys of the coast ranges as far north as Fort Lane in Oregon.” Fort Lane was located on the eastern flank of Blackwell Hill between Gold Hill and Central Point, Oregon. In 1917, Earl Marshall located “eight or ten little trees scattered over say maybe a quarter of an acre, trees maybe 20 feet tall in a pasture southwest of Ruch.” When he returned in 1925 the trees had been cut down. Oliver Matthews found a single tree near Rock Point and Gold Hill in 1945. This tree was later cut down by the highway department and was dated back to 1919. In 1955, logger Dan Rigel found trees north of Sam’s Valley and in 1958 near Blackwell Hill and the old Fort Lane Site. Small populations have been found since that time, many have been cut down or burned. The tree near Little Grayback in the Applegate Watershed was “discovered” in 1988 by a hunter named Dave Hoffer. It is currently maybe 30 + feet tall and maybe 15″ DBH. Gray pine is acknowledged in the newest edition of “Rare plants of Southwest Oregon.” The Little Grayback population appears to be identified.

Finally, the subalpine fir has not been found in the Applegate watershed, but it is nearby. A small population exists just east of the watershed on the north flank of Mt. Ashland. The Red Buttes population is just to the west of the Applegate River watershed in the headwaters of Sucker Creek, which drains into the Illinois River. It is a few small trees in a moist rocky bench near Tannen Mountain. Subalpine fir is almost in the Applegate Watershed, but we have to give credit to the Illinois River watershed and Ashland Creek for their rare conifers as well.