In recent years southwestern Oregon has experienced uncharacteristically intense heat and extreme temperatures with prolonged periods of drought. Throughout interior southwestern Oregon and the Applegate River watershed these specific drought events and “heat domes” have in turn triggered eruptive flatheaded fir borer mortality outbreaks.

In 2022 and 2023, the outbreak affected Douglas fir populations at lower elevations, predominantly on sunbaked south and west facing slopes, in areas where shallow, unproductive soils favor chaparral or oak woodland, and in areas with relatively low precipitation levels adjacent to the valley floor or on exposed foothill slopes. Ironically, mortality has often also been concentrated in conifer forests subjected to BLM “forest health” commercial thinning (i.e. logging) operations over the past 30 years.

Unlike 2022 and 2023, the spring, summer and late fall of 2024 brought very little conifer mortality, demonstrating that the eruptive beetle outbreak has subsided. Even the casual observer can drive Highway 238 through the center of the Applegate Valley today, and see very little conifer mortality; whereas, in 2022 and 2023, the hills were streaked in “red stage” beetle mortality. The abundant fall rain this past month continues to mitigate the concerns of beetle proliferation and significant tree mortality; however, BLM is ignoring that the eruptive outbreak has passed and assumes that there will be elevated mortality rates in the next few years, despite dramatically changed circumstances.

Unfortunately, BLM has responded to this tree mortality event with post-disturbance “salvage” logging in stands either affected by recent beetle mortality or in living, green stands that survived the outbreak, an approach the BLM recently implemented in the Lickety Split Timber Sale, with devastating impacts. In the Lickety Split Timber Sale whole slopes of both living and dead trees were cleared above the Little Applegate River, and its tributary Lick Gulch, in large clearcuts and industrial logging operations.

Recently, this approach was taken a step further when the BLM approved the Boaz Salvage Timber Sale on the ridgeline dividing the Upper Applegate and Little Applegate Valleys. In the Boaz Timber Sale, both stands with significant mortality and whole stands of living, green Douglas fir trees are proposed for clearcut logging. According to BLM’s own data, the Boaz Salvage Timber Sale would retain, on average, only 3.3 trees per acre, while logging many thousands of mature trees that survived the beetle outbreak.

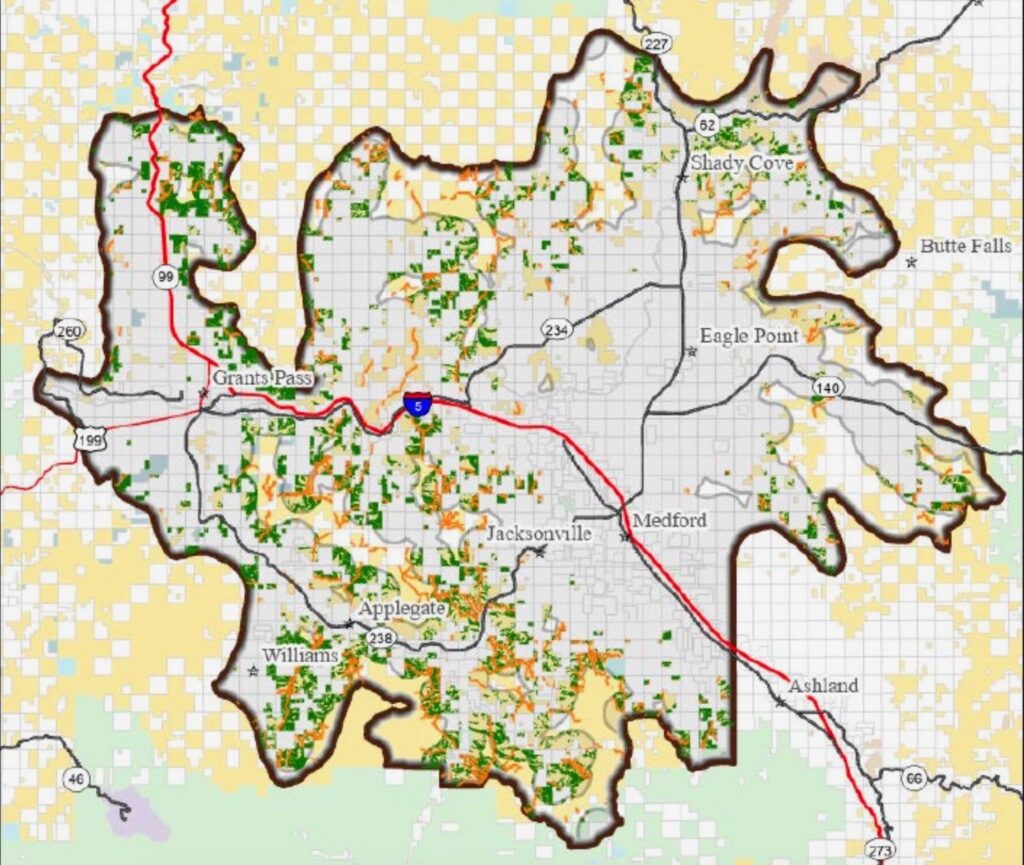

The BLM is now also proposing the so-called Strategic Operations for Safety (SOS) Programmatic EA, which would allow the BLM to log virtually at will, without any meaningful scientific analysis or public comment, across approximately 840,000 acres of Medford District BLM lands. The project area was designed to encompass the more arid, lower elevation habitats in interior southwestern Oregon, and it therefore surrounds many local communities, including Eagle Point, Shady Cove, Gold Hill, Rogue River,Grants Pass and communities throughout the Applegate Valley. It also includes a total of approximately 254,000 acres of “eligible treatment areas” that could be logged.

Alternative 2 of the SOS Project proposes to log up to 15,000 acres and build up to 20 miles of new “temporary” road every five years. The prescriptions allow for the removal of both live and dead standing trees in all age and diameter classes, and in virtually all Land Use Allocations. This includes Late Successional Reserve forest set aside to protect Northern spotted owl populations and their old forest habitat. It also proposes significant logging in Riparian Reserves designated to protect water quality and riparian habitats, as well as in Areas of Critical Environmental Concern meant to protect some of the Medford District BLM’s most important, diverse, and intact habitats.

The SOS Project specifically allows the BLM to target stands with as little as 10% cumulative mortality, claiming these habitats have been heavily affected by beetle mortality. Alternative 2 would allow the BLM to both log adjacent to “linear features,” like roads and ridgelines, within one mile of homes, and as “area” treatments focused on commercial timber production. Either way, the timber sales implemented under the SOS Project would heavily log mature stands with living, green forest canopy down to as low as 20 square feet of basal area.

This translates to clearcut logging with a handful of “seed” trees per acre. For example, a 30″ diameter tree is approximately 5 square feet of basal area and retaining 20 square feet of basal area means retaining only four, 30″ diameter trees per acre. Conversely, a 20″ diameter tree is about 2.2 square feet of basal area, so retaining 20 square feet of basal area means retaining only nine, 20″ diameter trees per acre. (source: USDA Basal Area/Tree Per Acre guide)

The BLM claims this logging must occur to support public safety and reduce fire risks; however, many of the trees identified as “dead and dying” are living trees which do not pose public safety risks, and logging these trees to the levels proposed will actually dramatically increase fire risks.

The SOS Project also claims these trees must be logged to capture economic value from “dead and dying” trees subjected to flatheaded fir borer infestation and imminent mortality — but many of the trees targeted for logging include living, green trees without signs of beetle infestation.

Scientific research has shown that trees surviving large scale beetle outbreaks often contain unique genetic traits that may make them more resilient to drought, intense heat and future beetle outbreaks. This makes their retention particularly important for climate adaptation, for forest regeneration and for the retention of existing mature stands. (Six. 2018) Yet, thousands of acres of these forests would be logged in the BLM’s SOS Project, all without scientific review or meaningful public involvement.

Scientific studies conducted throughout the West have shown that beetle mortality patches, even at a relatively large scale, do not increase fire risks or fire severity, and may, in fact, reduce them. (Hart 2015., Meigs, 2016, Harvey etal. 2014, Donato. 2013) At the same time, research conducted on Medford District BLM lands has shown that the types of logging proposed tend to increase future fire risks through the loss of canopy cover, the removal of large fire resilient trees, the accumulation of logging slash, the regeneration of dense, even-aged, highly flammable vegetation, and by altering cool, moist micro-climate conditions. (Zald. 2018. Lesmeister. 2019)

The snags and downed logs that remain after relatively severe natural disturbance events, like beetle mortality outbreaks, are also important “biological legacies” and become a “requisite for maintaining long term forest growth.” Research shows that “in the Klamath Mountains conifer seedling performance can depend on the ability of the soil to retain moisture and support nitrogen fixing and ectomycorhizal organisms. Removal of large amounts of organic material may result in difficult reforestation of these thin, droughty, and infertile sites. (Amaranthus.1989)

The snags provide structural diversity, important wildlife habitats, shade for forest regeneration, and create continuity between the forest conditions before and after a beetle mortality event. Additionally, as these snags fall to the forest floor they become downed logs, which are also important for structural complexity and wildlife habitat, while also creating microclimates that are important for forest regeneration, as water retention reservoirs holding up to 25 times more water than adjacent forest soils, and as habitat for the mycorrhizal fungi required by many native conifer species. (Amaranthus. 1989).

Logging these biological legacies (e.g. snags and live trees) would have lasting consequences, and very few benefits to surrounding communities. In fact, the snags or dead standing trees removed will be done at an economic loss, or as, at best, break even timber sales, and that’s why the BLM has padded the economics of these sales by including abundant living, green trees, which are sold at low value salvage prices for the economic benefit of the timber industry.

The logging of these green trees under a so-called “salvage” sale is not only dishonest and inappropriate, but it will compound the impacts following the recent beetle events and the loss of mature forest cover already occurring in the region.

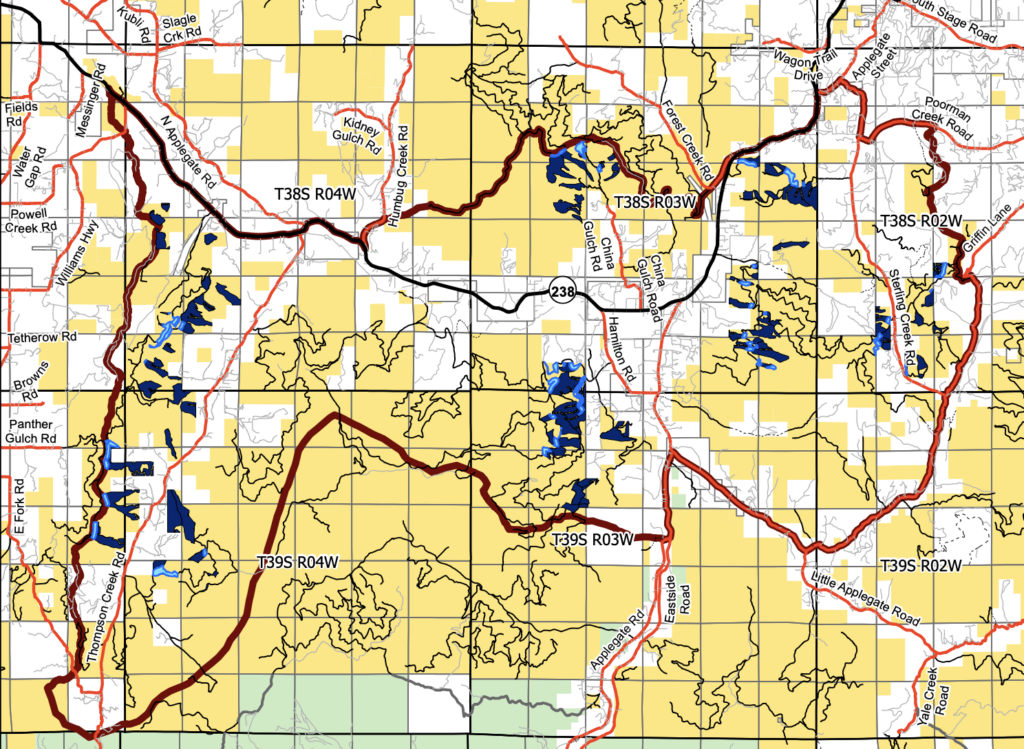

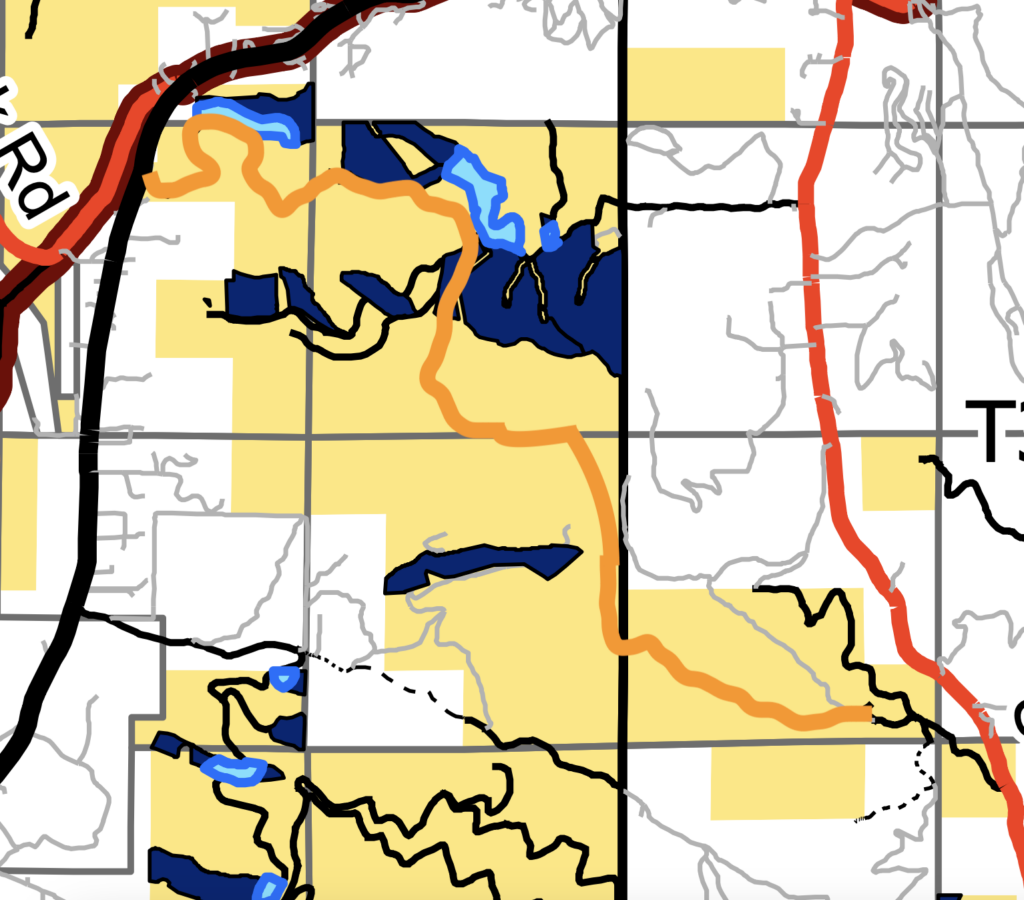

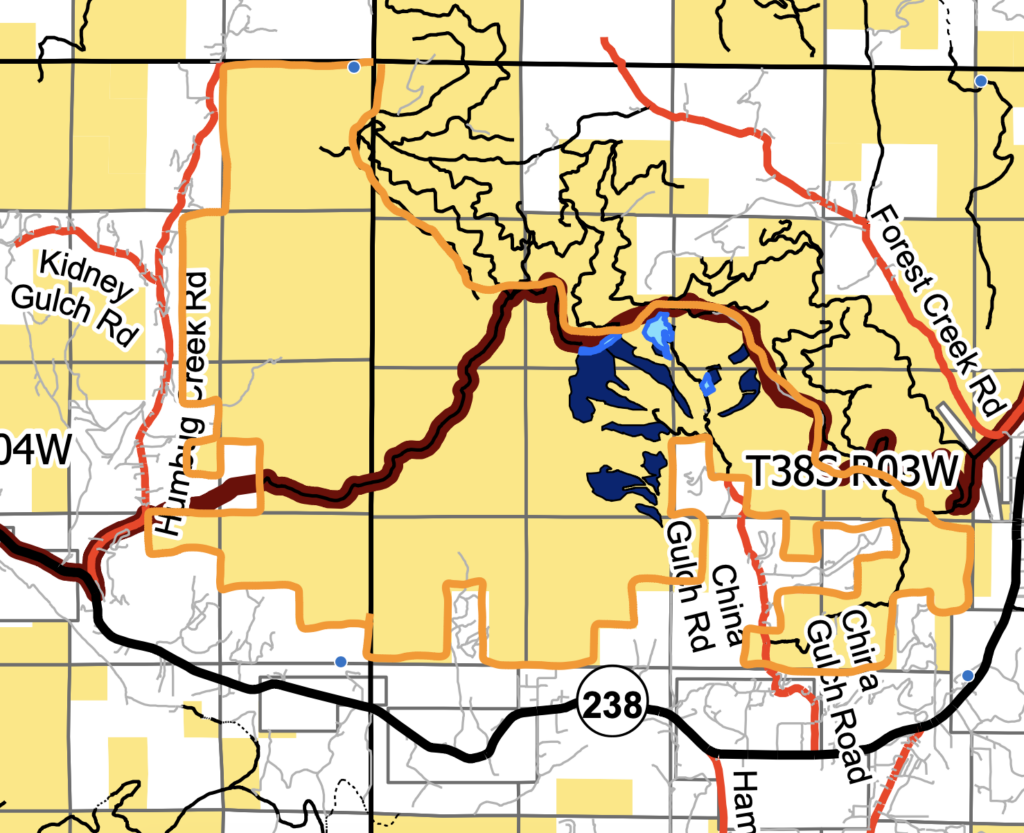

To make matters worse, the BLM has proposed to start this damaging project in the Applegate Valley with the first timber sale called “SOS Project 1,” which includes extensive logging on Thompson Creek, around Ruch, on Sterling Creek, in the forests along and adjacent to the East Applegate Ridge Trail, and in the Wellington Wildlands, a cherished wildland and 7,500-acre roadless area located between Ruch and Humbug Creek, at the heart of the Applegate Valley.

Many of the forests proposed for logging have not been significantly affected by beetle mortality and are being mischaracterized as “salvage” logging. Weaponizing the public’s fear of climate change, fire and beetle mortality, the BLM has initiated a campaign of Orwellian misinformation claiming they must clearcut or virtually clearcut living, green stands to save them from future mortality — but the only certainty of mass tree mortality is the authorization of the BLM’s SOS Project and the green tree logging it would unleash.

Like many of the projects recently proposed by the Medford District BLM—and shut down in the courts—the agency is once again attempting to eliminate any meaningful scientific review, site specific, project level analysis, and public comment opportunities that would otherwise encourage accountability and/or some level of scientific rigor. The SOS Project should be opposed and all post-disturbance logging should be limited to true hazard trees: truly dead standing trees along regularly used BLM roads.

The BLM is currently taking public comments on both the SOS Project and SOS Project 1. Use the information in this post and below in the talking points to provide public comment for these damaging logging projects.

SOS Project Talking Points:

-No living, green trees should be logged in the SOS Project. The vast majority of these trees are not infested with flatheaded fir borer beetles and do not meet the criteria for “dead and dying” trees.

-Current mortality rates have dramatically declined since 2022 and 2023 due to the eruptive nature of beetle mortality events and shifts in regional weather patterns. This means that the potential for tree mortality has dramatically decreased and the assumptions surrounding imminent mortality are unfounded. Current analysis in the SOS Project erroneously ignores that the recent eruptive mortality event has subsided.

-The removal of living tree canopy will only increase fire risks by opening up stands to increased wind and solar exposure, while encouraging dense, highly flammable even-aged regeneration of brush, hardwoods and conifer species. This understory response or increase in young, even-aged growth, along with artificial tree planting, has been shown to dramatically increase fire risks in affected stands.

-Removing living, green trees that survived the recent beetle mortality events will reduce forest cover and remove genetically resistant trees that have an increased ability to survive beetle outbreaks. These same trees also aid in the regeneration of affected habitats with genetically adapted and highly resilient trees.

-Logging beetle mortality patches will disrupt forest succession, damage forest regeneration, impact soils, spread noxious weeds, remove important wildlife habitats, and degrade complex early seral plant communities supporting incredible biodiversity.

-2024 Aerial Detection Surveys have not been disclosed or made publicly available, and were not included in the SOS analysis. This is important because these surveys would show a dramatic decline in Douglas fir mortality across the region in 2024, yet the agency is refusing to provide information or publish the results of its publicly funded survey. These surveys must be completed, made public, be included in both project analysis, and available to inform public comment before project approval. Withholding this information from the current analysis is irresponsible and inappropriate.

-The recent mortality in southwestern Oregon and climate trends going forward show that the productivity of many forests are not sufficient to justify the designation of “Timber Harvest Land Base,” and the entire planning area should be removed from this land use designation. Sustained yield logging is inappropriate, timber yields and growth rates cannot be reliably sustained, and other public land values cannot be maintained if timber is being unsustainably harvested.

Follow this link and click on the “participate now” button to comment. Make your comments by January 6, 2025

SOS Project 1 Talking Points:

-Repeat the same talking points as above for the SOS Project and include the specific concerns below for the SOS Project 1 proposal.

-The units proposed for logging in the Wellington Wildlands are highly controversial and should be canceled from further consideration in the SOS Project 1. They are also located on the proposed trail corridor for the Center Applegate Ridge Trail, which has been promoted by the Applegate community for over a decade and would be damaged by industrial logging activities.

-The units along the highly popular East Applegate Ridge Trail will impact scenic, biological, and recreational values and are incompatible with the East Applegate Ridge Extensive Recreation Management Area. All units adjacent to or surrounding the East Applegate Ridge Trail should be canceled.

-The Woodrat Mountain and Woodrat Mountain Gliding Site’s Special Recreation Management Area contain unique recreational opportunities, world-class hang gliding opportunities, and highly scenic values which would be impacted by the types of logging proposed. Units surrounding Woodrat Mountain should be canceled.

-“Salvage” logging, especially when significant green tree removal is involved, will increase fire risks, impact nearby communities, degrade habitat values, damage scenic viewsheds, and impact the local outdoor recreation and amenities based economy of the Applegate Valley.

Follow this link and click on the “participate now” button to comment. Make your comments by January 6, 2025

References:

Amaranthus, M.P. & Parrish, D.S. & Perry, David. (1989). Decaying logs as moisture reservoirs after drought and wildfire in Stewardship of soil, air and water resources. Proceedings of Watershed 89. 191-194.

Donato, D.C., Harvey, Brian J., Romme, William H., Simard, Martin, Turner, Monica. 2013, Bark Beetle Effects on Fuel Profiles Across a Range of Stand Structures in Douglas-fir Forests of Greater Yellowstone. Ecological Applications, 23 (1), 2013 pp. 3-20

Hart, Sarah J. Schoennagel, Velden, Thomas T., Chapman, Teresa B. 2015. Area burned in the Western United States is Unaffected by Recent Mountain Pine Beetle Outbreaks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science UnitedStates of America. Vol. 112, No. 14, 4375–4380, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424037112

Harvey, Brian J., Donato, Daniel C., Turner, Monica G., 2014. Recent Mountain Pine Outbreaks Wildfire Severity, and Postfire Tree Regeneration in the US Northern Rockies.Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. Oct 21, 2014 111 (42): 15120-15125

Lesmeister, Damon., Sovern, Stan., Davis, Raymond., Bell, David., Gregory, Matthew., &Vogeler, Jody. 2019. Mixed Severity Wildfire and Habitat of an Old Forest Obligate. Ecosphere Vol. 10, Issue 4, April 2019 https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2696

Meigs, Garrett W., Zald., Harold S., Campbell, John L., Keeton, Williams S., Kennedy, Robert E., 2016. Do Insect Outbreaks Reduce the Severity of subsequent fires?Environmental Research Letters, 2016; 11 (4): 045008 DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/045008

Six, Diana L., Vergobbi, Clare., Cutter, Mitchell., 2018. Are survivors different? Genetic-based selection of trees by Mountain pine beetle during a climate change-drive outbreak in a high elevation forest. Frontiers in Plant Science. July 2018. Volume 9, Article 993 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00993/full

Zald, Harold S. & Dunn, Christopher J. (2018) Severe fire weather and intensive forest management increase fire severity in multi-ownership landscape. Ecological Applications 0(0), 2018. Pp 1-13