Flat headed fir borers, engraver beetles, and other wood and bark boring insects

Triggered by extended droughts, a significant lack of persistent winter cold snaps, stifling summertime heat domes, and a changing climate, flat headed fir borers and fir engraver beetles have become very active across interior southwestern Oregon. In fact, populations of these native wood boring beetles have exploded in recent years, creating significant Douglas fir mortality throughout the region.

A visceral sign of climate change, the mortality reached epidemic proportions in 2022 and 2023, when flat headed fir borers could literally be heard chewing through stands of Douglas fir in the foothills of southwestern Oregon.

Mortality was occurring in large patches at lower elevations, especially on droughty sites, harsh exposures, sites with poor soils, sites more conducive to oak woodland, chaparral, or mixed hardwood stands, and in many previously implemented “forest health” logging or commercial thinning projects.

Since the 1990s, the Medford District BLM and Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest have been implementing landscape-scale logging, or commercial thinning projects, intended specifically to increase “forest health” and resilience to both drought and beetle mortality; however, in many locations these “restoration” thinning projects have had the opposite effect, and both the false claims used to justify the logging, and the forested habitats they have “treated” have begun to unravel.

Ironically, many of these previously implemented federal land timber sales have sustained significant flat headed fir borer mortality and are at the center of the region’s beetle induced Douglas fir mortality event. This includes numerous timber sales implemented by the BLM in the past 30 years in the Applegate Valley and the Ashland Forest Resiliency (AFR) Project in the Ashland Watershed. At the same time, droughty conditions and extreme temperatures are also increasing pine mortality associated with various bark beetles in both thinned and unthinned stands.

At best, the previous commercial thinning treatments failed to create the resilience or restoration predicted by the BLM and USFS in each timber sale’s scientific analysis and approval documents (e.g. Environmental Analysis, Decision Record, etc.), and the agencies need to stop promising outcomes they can’t actually create through logging.

At worst, the logging was actually responsible for the scale of the beetle outbreak by weakening whole stands of trees, and the agencies need to stop large-scale commercial logging that is contributing to the loss of regional forests.

The reality is likely somewhere in between. Climate conditions can trigger the outbreak, while in some places previous commercial thinning or logging operations have damaged soils, damaged trees, increased aridity, increased edge effect, increased air temperatures, made stands more susceptible to beetle impacts, encouraged beetle populations to expand, and contributed quite significantly to the mortality event.

In many ways, the BLM has been an active contributor to both the current climate crisis and the recent beetle mortality event, by creating extensive logging related carbon emissions that fuel climate change. Recent research found that commercial logging and timber manufacturing is the largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions in the state of Oregon (Law. 2018), while regional research shows that commercial logging is responsible for 80% of the Forest loss in Oregon and Washington combined. It also found that logging in Oregon and Washington constitutes 67% of all forest loss in the 11 Western states where fire and beetle mortality are most acute. This makes logging, not beetle mortality, the most significant threat to the forests of the West, and in particular the most significant threat to forests in the Pacific Northwest. (Berner. 2017).

BLM’s Response: The SOS Project

In response to the recent increase in beetle mortality, the Medford District BLM has proposed the Strategic Operations for Safety (SOS) Project, a large-scale “salvage” or post-disturbance logging project sprawling across rural southwestern Oregon. Proposed under the pretext of public safety, the focus of the project would actually be to opportunistically log 1,000 acres, and roughly 10 million board feet of dead and supposedly “dying” trees to meet the agency’s 2024 timber targets.

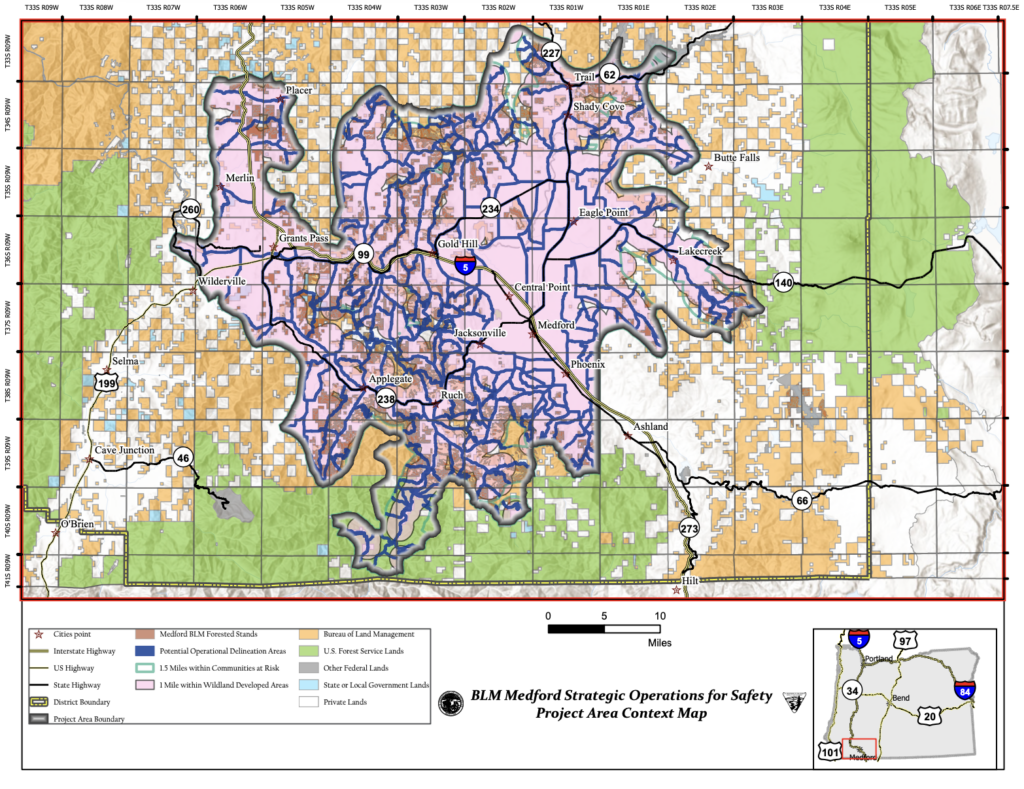

Currently the BLM has identified a massive planning area sprawling across the BLM lands surrounding both the Rogue and Applegate Valley. Unfortunately, what the agency has not done, is identify where within this vast landscape that post-disturbance logging would actually occur. According to the Scoping Notice for the Strategic Operations for Safety Project (SOS Project), the BLM would log approximately 5,000 acres in still undisclosed locations.

These operations could occur along BLM roads, in what the BLM calls Potential Operational Delineation (POD) areas, and within 1 mile of developed areas or homesteads. They could also be implemented in Riparian Reserves, Late Successional Reserve (LSR) forests, along hiking trails and in recreation management areas, degrading the values these areas were designated to protect.

The agency claims this logging is benign or even beneficial, and is necessary for both public safety and future fire containment. Yet, the agency proposes logging over 500′ on either side of BLM roads and so-called POD areas, far beyond what can be credibly called “hazard tree” logging, and far beyond what is necessary for future fire containment. As currently designed the project is an excuse to log, not a valid public safety or fire risk reduction project.

The BLM also proposes logging both dead standing, beetle killed snags, and live, green trees that survived the beetle outbreak. Yet, these surviving trees contain either high genetic resistance, or grow in favorable microclimate conditions, allowing for their survival and persistence. Removing these trees will generate short-term profits for the industry, and provide board footage for the BLM’s annual timber quota, but will undermine long-term forest and climate resilience.

Snags provide important wildlife habitat and are the foundation of both stand recovery and future forest or woodland complexity. In fact, research conducted in southwestern Oregon following the 1987 Galice Fire found that large downed wood retained “tremendous quantities of water… Even after 77 days without rain and an intense wildfire.” The researchers literally wrung water out of downed logs which had 25 times more moisture on a weight basis than did soil samples. Researchers suggested that this moisture “may help pioneering plants become established where soil moisture is low,” making it “a requisite for maintaining long term forest growth” in the region. The author explains, “in the Klamath Mountains conifer seedling performance can depend on the ability of the soil to retain moisture and support nitrogen fixing and ectomycorhizal organisms. Removal of large amounts of organic material may result in difficult reforestation of these thin, droughty, and infertile sites.” (Amaranthus, 1990)

Following a significant mortality event, snags become the only large wood this system will produce for decades or even centuries, creating structure, diversity, habitat and favorable growing conditions for young, regenerating forests. Large, relatively rot resistant species can persist, provide continuity, and play functional roles in the regenerating ecosystem for centuries, if not removed in post-disturbance logging operations.

The reality is, that the BLM has a stocking requirement after “regeneration” logging. This usually means that they have to plant trees after clear cutting an area. This means that the “regeneration” logging proposed in the SOS project will be followed by tree planting and plantation development, creating dense, young, heavily simplified, and highly flammable vegetation that has been proven in multiple regional wildfires to increase fire severity and spread.

As currently designed the SOS Project will leave a lasting biological impact, provides little public safety benefit, and will produce low value timber that can only be implemented at a deficit to the taxpayer. Our forests and climate are sending out an SOS, and unfortunately, the BLM is responding in the only way it knows how: with a new timber sale to supposedly “fix” the problems the last one created. An endless cycle that needs to end for the sake of our forests and climate.

COMMENT NOW on the SOS Project.

Talking points for public comment:

- The project proposal lacks specificity, precluding meaningful public comment, agency analysis, and the disclosure of impacts as required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Site specific unit boundaries must be identified to conduct a valid scientific and public analysis.

- The proposed logging of dead or dying trees up to 500′ from roads and PODS serves no public safety purpose. No trees in our area grow 500′ tall, and therefore, cannot pose a safety risk to roads 500′ away. Tree and snag felling for public safety and fire suppression purposes should occur no more than 150′ from main system, high-use BLM roads.

- Logging dead or dying trees up to 1 mile from developed areas serves no public safety purpose and will not reduce fire risks unless the the tree felling is limited to areas within 150′ of homes or developed areas, and within 150′ of ingress/egress roads.

- Tree removal from the site is unnecessary and serves no public safety purpose. Once felled, a valid hazard tree 150′ or less from a high-use BLM road has been fully mitigated of all public safety risks. Trees that pose actual public safety risks could be felled, but tree yarding and removal is necessary, especially because much of the low value dead standing material will be sold at a loss to the public. Trees felled into the road could be removed if necessary, but trees felled onto the slopes should be retained and left on site for biological values.

- Standing snags and large downed trees are important for carbon storage, soil development, forest and woodland regeneration, habitat, water retention, and are the foundation for future forest complexity. These biological legacies should be retained on site whenever possible. Large downed wood has been show to be essential for stand regeneration and serves to dampen fire activity.

- No live trees that survived the recent beetle outbreaks should be felled or removed in the project area. These trees likely contain genetic or situational advantages, that allow for beetle and drought resilience. These are the most site-adapted trees, will encourage resilience and are preferable for forest or woodland reestablishment. The BLM should maintain these living trees for seed production and regeneration as well as habitat value.

- Tree felling and removal should not take place in Riparian Reserves, and only valid hazard tree felling within 150′ of high-use BLM roads should be considered in Late Successional Reserve (LSR) forest.

- The BLM should not build new roads in the SOS Project.

All comments must be received by January 7, 2024

For more information: SOS Project Website

Click on “Participate Now” to comment

To comment send an email or letter to:

By email: BLM_OR_MD_Safety_EA @blm.gov

-or-

By mail or delivery service:

Attn: Strategic Operations for Safety EA

Medford District BLM

3040 Biddle Road

Medford, Oregon 97504