In our last blog post, we explored the connection between BLM logging operations in the Applegate Valley and elevated levels of beetle mortality in recent drought events. We also examined the BLM’s currently proposed SOS Project which would log up to 5,000 acres of beetle affected forests throughout southwestern Oregon. This logging would include the removal of both live and dead standing trees, and in many cases will result in large-scale clearcut logging.

As a follow up to this previous post, we are now exploring two recent examples of so-called “salvage” logging in stands with varying levels of beetle mortality. Although you often hear land managers claim that these salvage logging treatments are focused on “fuel reduction” and “forest health,” the timber sale marks and the actual timber sale outcomes tell a very different story.

Salvage logging, by definition, is about recovering the economic value of dead trees, and most scientific studies have proven salvage logging to be ecologically damaging.

Below we will explore the actual result of these commercial logging, and often clearcut logging operations. Our case studies will include the Lickety Split Timber Sale implemented by the Medford District BLM in the Little Applegate Valley, and the helicopter logging recently approved by the city of Ashland, Oregon on city owned forest and park lands.

Lickety Split Timber Sale, Little Applegate Valley

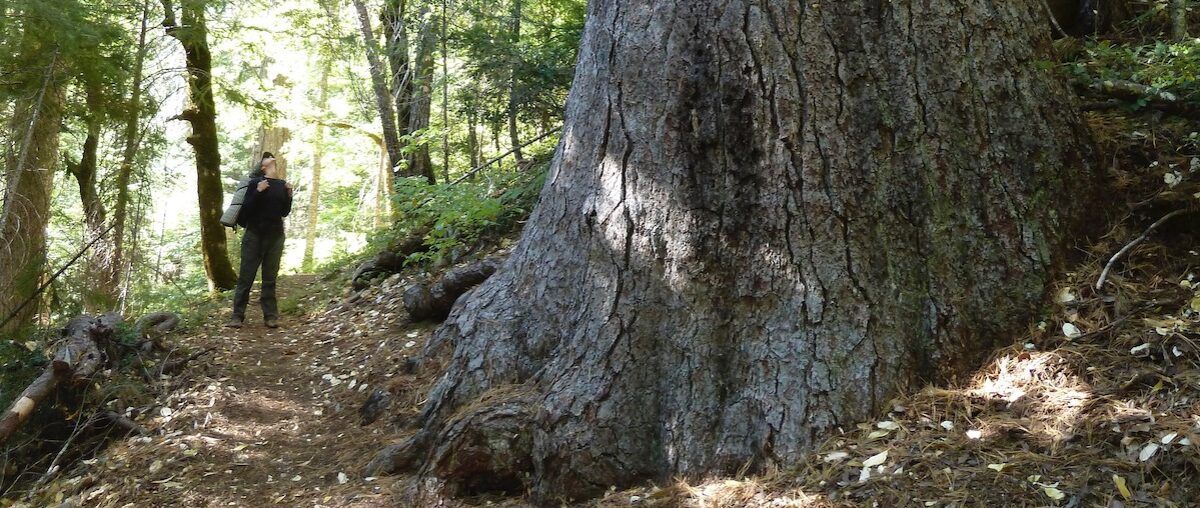

While the BLM recently led a public field trip to greenwash their SOS Project logging proposals, they have at the same time, been clearcutting and otherwise heavily logging large swaths of public land in the Little Applegate River watershed in the Lickety Split Timber Sale. This salvage logging project removed both dead standing, beetle killed trees, and large, green trees that survived the beetle outbreaks.

These living, green trees support favorable genetic traits that could naturally regenerate or reforest the beetle affected stands with drought and beetle resistant trees; however, in the case of the Lickety Split Timber Sale, the BLM logged many of these surviving trees, removing the naturally resistant seed trees and undermining the selective pressures and evolutionary processes that build future resilience in our local forests.

Just like other recent Medford District BLM salvage logging projects, the Lickety Split Timber Sale was implemented within stands that had been previously thinned for “forest health” and to “increase resilience,” but have instead become more susceptible to drought and beetle mortality affects. In this case, the salvage logging is occurring within the 2013 O’lickety Timber Sale, purchased by Murphy Timber Company and logged by Bull Creek Logging, as well as the Lick Stewardship Project, which was purchased and logged by Lomakatsi Ecological Services (the for-profit wing of the Lomakatsi Restoration Project). Both of these projects were illegally over-cut when they were logged due to excessive tree marking by the BLM, have subsequently sustained high levels of mortality, and were salvage logged in the Lickety Split Timber Sale.

In response to the most recent mortality in these stands, the BLM has removed nearly all overstory canopy, and in many locations, has clearcut both dead standing and living green trees. The result of the Lickety Split Timber Sale in many units looks like a clearcut, functions like a clearcut, will be replanted in plantation stands like a clearcut, and will both damage habitats and increase fire risks like a clearcut.

Although the BLM often claims these salvage logging operations will favor and encourage hardwoods, oaks, pines and more drought resistant native vegetation, again, when you compare their claims to the actual outcome of their projects, it’s a very different story. In the Lickety Split Timber Sale, the agency removed not only living and dead standing conifer trees, but also cut, damaged, or otherwise destroyed nearly every hardwood (madrone, black oak, white oak, etc.) in the timber sale units. This left virtually nothing to replace the beetle killed stands. Additionally, the widely spaced and heavily isolated conifer trees, or very occasional hardwood tree that survived the logging operation, are now highly susceptible to increased windthrow during high winds or heavy snow events.

In addition to projects like the Lickety Split Timber Sale, the Medford District BLM is administratively reclassifying many beetle killed stands as “young stands.” This allows the BLM to treat these stands using “pre-commercial” thinning prescriptions which remove virtually all hardwoods and purposefully reintroduces even-aged, plantation style forestry, instead of allowing the more resilient hardwoods, residual conifers, and naturally regenerating forests to develop after the beetle mortality events. Both the removal of more resilient, but less commercially valuable species, and the artificial reforestation or tree planting that follows such heavy industrial logging, will degrade habitats, simplify forest structure, reduce stand resilience and dramatically increase fire risks.

Don’t be fooled by the BLM’s rhetoric, the Lickety Split Timber Sale demonstrates exactly what the BLM’s proposed salvage logging in the SOS Project will create: clearcuts, heavy logging slash, extensive soil damage, stream sedimentation, an impediment to natural regeneration, new plantation stands and significantly decreased habitat values across broad landscapes. Fire risks will also increase in many of the forests that surround our communities due to the even-aged regeneration practices associated with clearcut logging and salvage logging operations.

The result of this project is quite literally clearcut, and the so-called benefits BLM speaks of are simply not part of the actual outcome from these logging operations. Rather than encouraging a natural, diverse, dynamic vegetative recovery following the recent mortality outbreaks, BLM is degrading habitats, developing plantations, and releasing naturally stored carbon through tree and snag removal operations. Rather than making our forests more resilient, the BLM and its salvage logging practices are fueling the climate and biodiversity crisis.

City of Ashland Helicopter Salvage Logging

The city of Ashland, under the leadership of Ashland Fire and Rescue, Wildfire Division Chief Chris Chambers, and with a $150,000 subsidy from the Lomakatsi Restoration Project, has also proposed a large scale helicopter salvage logging project on city owned lands, including much of the Ashland Watershed’s beloved trail system.

Similar to the salvage logging projects recently proposed or approved by the BLM, this project will “salvage” tree mortality that has occurred since previous “forest health” logging operations were implemented. Most of this project is proposed in previously “treated” stands, many of which were commercially thinned with helicopters during the Ashland Forest Resiliency Project.

Although often characterized as a beetle mortality or “salvage” logging project, the city has marked acres and acres of live, green trees that survived the recent beetle outbreaks. In fact, in our monitoring of the project it appears that more live trees will be logged than those that were recently killed by beetle infestation.

In fact, the timber sale mark (implemented for the city of Ashland by the Lomakatsi Restoration Project) did not appear to achieve overtly ecological objectives. Large snags with potential commercial value, often including the largest snags in a stand, are marked for removal. This often includes the biggest, most important wildlife snags and isolated snags that pose no risk to public safety or future fuel loading. In many cases, snags would be clearcut, or virtually clearcut, and stands of live, green trees would be heavily thinned, leaving them susceptible to the same problems, and suffering from the same fragility that the original Ashland Forest Resiliency Project thinning operations have created.

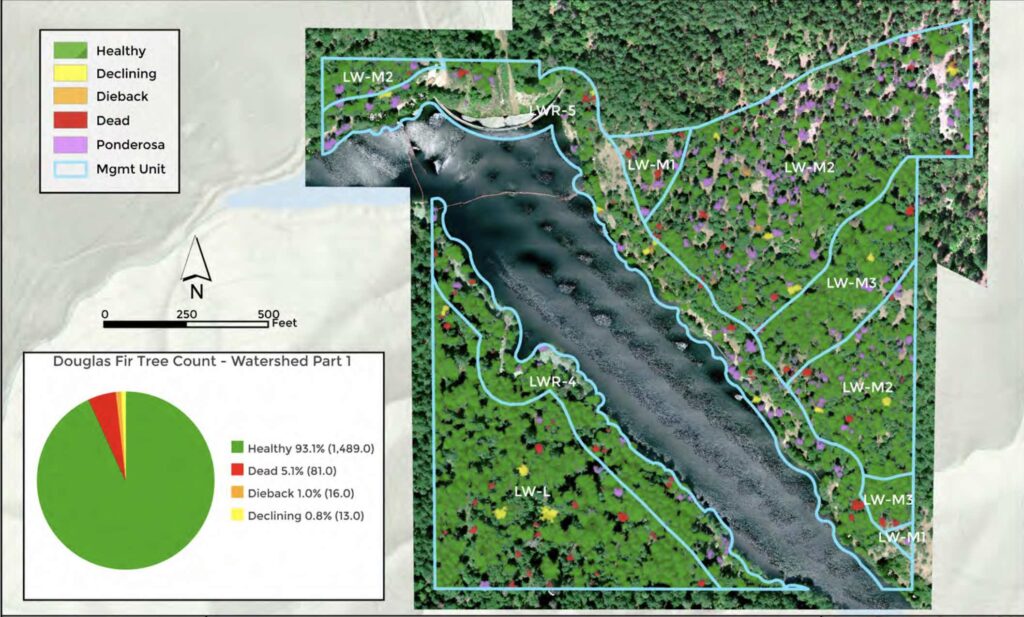

Recently, the Ashland City Council approved the logging of the Reeder Reservoir area to offset the extensive public cost of this largely unnecessary project. According to recent city drone surveys 93% of the Douglas fir trees in this area are healthy. Not exactly an emergency, the logging around Reeder Reservoir, the city of Ashland’s water supply, is being conducted to enhance the economic, not the biological value, of this shortsighted timber sale. Other areas supporting between 68% and 78% healthy Douglas fir trees would also be logged in this proposal, including Ashland’s beloved Siskiyou Mountain Park, along the White Rabbit Trail, along the Bandersnatch, Snark, and Red Queen Trails, in the Hitt Road/Acid Castle area, and on other portions of city owned land.

In fact, the city surveyed approximately 800 acres of publicly owned city park land and recreational areas using drone technology. On this 800 acres it found only 2933 dead trees or approximately 3.6 dead trees per acre. Although in some areas mortality has been more extensive, the overall effect is relatively minor, and perhaps even beneficial in the long run.

This pulse of beetle mortality would, if left unlogged, provide a necessary input of snags and downed wood in forests that are currently largely deficient in both. The beetle mortality naturally thinned forest stands, created gaps for hardwood and conifer regeneration, provides important habitat values, and significantly contributes to habitat heterogeneity.

Utilizing what we call “fear based forestry,” Chris Chambers has been quoted in local newspapers stating that beetle mortality threatens public safety, will increase fire risks, and even that dead standing trees may fall into Ashland Creek, somehow threatening downstream communities. He has also claimed that beetle mortality is threatening to convert the forests of the Ashland Watershed into grassland or shrubland habitat. Unfortunately, neither the science that has studied beetle mortality events, the severity of this particular beetle event, nor the facts of this project support this narrative.

Ironically, despite the claims of “firmageddon” in the media and the fear-based messaging of project partners, the cumulative mortality created by previous commercial thinning operations in the Ashland Forest Resiliency Project, and the additional green tree logging proposed in the Ashland watershed under the guise of timber salvage, has killed or will kill, far more trees than the recent beetle outbreak in the Ashland watershed.

The natural disturbance (in this case beetle mortality), although potentially accelerated by climate change and drought, is within the range of variability for this landscape and has likely happened before. Habitats in the transitional climate of southwestern Oregon are significantly influenced by natural disturbance episodes including drought, beetles, fire, snowloads, wind storms, and even native pathogen outbreaks. Plant communities shift in response to these disturbance episodes and mortality leaves important biological legacies that provide habitat, support complexity, hold moisture, build soil, and maintain continuity between habitats and successional stages.

Additionally, while the beetle mortality event killed genetically susceptible, less resilient trees and forests, the logging proposed will remove green, living trees that demonstrated significant resilience by surviving these droughts and subsequent beetle mortality events. These survivors may contain significant genetic adaptations important for building future resilience to drought and beetle outbreaks in our local forests, but unfortunately, the City of Ashland plans to remove many of them in helicopter logging operations.

Instead of focusing on legitimate hazard tree removal along forest roads, at trailheads, around public infrastructure and directly adjacent to communities, snag and live tree removal will be widespread throughout the watershed and will occur in relatively remote portions of these city owned properties. In many cases this will include stands far from trails, trailheads, or developed infrastructure. In these locations, public safety risks are either very minimal or non-existent. In fact, the Reeder Reservoir parcel is largely closed to the public and thus, no public safety risk can be credibly claimed. Instead, the logging proposed on the Reeder Reservoir property is purely economically driven and the live, green timber will be used to subsidize and/or offset the removal of dead standing snags throughout city owned land.

Furthermore, tree and snag removal will impact the scenic value of local recreational trails turning portions of these trails like the Bandersnatch Trail and White Rabbit Trail into extensive stump fields. Snag and tree removal will reduce wildlife habitat in the area, remove important biological legacies, leave future stands deficient in snags and downed wood, and open stands up to both increased aridity, increased drought stress and increased fire risks.

Snag and tree removal will also impact future soil stability, soil productivity, and soil moisture availability by removing snags or low vigor trees that would provide for the recruitment of coarse downed wood. Coarse downed wood is a critical component of old-growth forests, and if we want old forest habitats, we need both downed wood and big standing snags.

As for the concerns of snags falling in Ashland Creek, the science shows that has been happening for thousands and thousands of years, and is indisputably a good thing for the creek, for fisheries, and for aquatic species of all types. The reason watershed councils across the region spend millions placing large logs into streams, is because it’s good for riparian health and fish! The recent beetle outbreak provided a pulse of mortality recruiting snags, downed trees and instream wood which supports soil, wildlife and watershed health.

Conclusions

Despite the claims of logging proponents, a heavy dose of greenwash, and a persistent public relations campaign, the current push to “salvage” beetle killed timber in southwestern Oregon comes with significant environmental consequences and climate impacts, and very few benefits. Most definitely not a restoration or fuel reduction treatment, the logging currently being implemented and proposed across the region will simplify, degrade, and diminish the resilience, beauty, and biodiversity found in southwestern Oregon’s unique, highly diversified forests.

Neither the logging approved in the Ashland watershed or the Applegate Valley has positive biological outcomes; neither will meaningfully reduce fire risks; neither will restore ecosystem function, and neither will achieve the lofty objectives claimed by the city or by the BLM. These projects and their numerous undesirable outcomes should inform the conversation about future salvage logging in the BLM’s proposed SOS Project and similar projects likely to be proposed by both the BLM and other land managers.

Despite the forest health rhetoric, salvage logging is the worst form of industrial logging, with perhaps the most significant and lasting environmental impacts because it is often implemented as clearcut or heavy industrial logging. It is also often rushed to the mill and poorly designed without sufficient site specific analysis or adequate design features to mitigate impacts. In the case of the Lickety Split Project, it was also implemented during the rainy season maximizing the projects impact on soils, hydrology, sedimentation and watershed health.

We encourage folks to get out when the logging is finished in the Ashland watershed, or go for a drive up Lick Gulch Road in the Little Applegate River watershed. The consequences of salvage logging, the singular economic focus, and the false narrative spun by its supporters will quickly become evident.

Directions to Lick Gulch Road and the Lickety Split Timber Sale: Drive highway 238 to beautiful Ruch, Oregon and turn south onto Upper Applegate Road. Follow Upper Applegate Road 2.9 miles to the intersection of Little Applegate Road. Turn left on Little Applegate Road and continue 4.9 miles to the pavements end and turn right on Yale Creek Road. Drive past a row of mailboxes, cross the Little Applegate River on a bridge and immediately turn left on the signed “Lick Gulch Road”, also known as BLM road 39-2-28 (denoted by a large brown BLM road sign). Follow this road past a few residences and onto BLM land. Immediately you will see Lickety Split Timber Sale units. Continue driving and turn right at the next intersection. You can drive this road for 3-4 miles driving in and out of timber sale units.